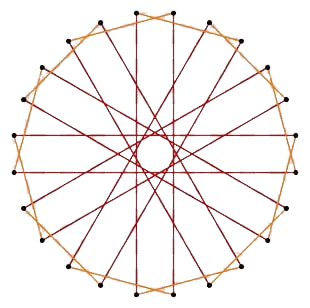

The Icositetragon — Designing with the 24-Sided Circle

In design practice, circles and squares dominate as the primary forms of order. Yet hidden between them lies a figure of quiet significance: the 24-sided polygon, known as the icositetragon. While it may sound abstract, this form offers designers a powerful way to explore balance, rhythm, and coherence in space.

The icositetragon divides the circle into 24 equal parts. Each segment carries an angle of 15 degrees—a division that recurs in music, mathematics, and even human biology. In music, 24 keys form the complete cycle of major and minor tonalities. In time, 24 hours mark the rhythm of the circadian day. In anatomy, the human spine connects 24 vertebrae before merging into the sacrum. The recurrence of 24 across disciplines suggests that it is more than a geometric curiosity—it is a structural constant of life.

When applied to design, the icositetragon offers a template for proportion and orientation. Dividing spaces or layouts according to its 24-fold rhythm allows designers to connect with natural cycles—of light, sound, and even physiology. For instance, lighting systems aligned to 15° increments can better match circadian rhythms, while spatial orientations based on 24-part symmetry have been shown to enhance wayfinding and reduce cognitive load.

Ancient builders hinted at this form. Many mandalas, rose windows, and sacred diagrams use 12- and 24-part divisions to encode rhythm and meaning. These geometries were not decorative alone; they trained attention, structured ritual, and supported coherence in collective experience. Modern neuroscience now supports what traditions intuited: rhythmic geometry can entrain human physiology, calming the nervous system and enhancing focus.

For today’s designers, the icositetragon is less about drawing a 24-sided polygon and more about recognizing rhythm as a design principle. Whether in the pacing of a façade, the sequencing of lighting, or the layout of communal space, 24-part coherence offers a framework to align design with human cycles. The result is not just visual order, but embodied harmony.

To design with the icositetragon is to acknowledge that geometry, time, and biology speak the same language. It invites us to see form not as static, but as rhythm—an architecture that resonates with the pulse of life.

References:

- Grant, R. E. (2024). Codex Universalis Principia Mathematica.

- Critchlow, K. (1976). Order in Space: A Design Source Book.

- Pallasmaa, J. (1996). The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses.

- Stevens, S. S. (1973). Perception and Measurement in Psychology.